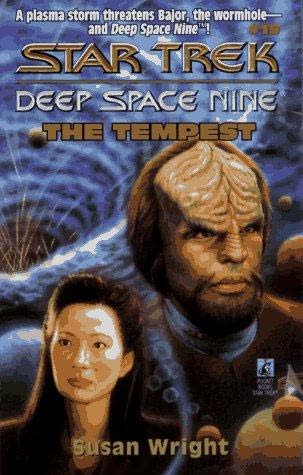

The Tempest

A plasma storm threatens Bajor, the wormhole—and Deep Space Nine!

- Stardate Unknown

- Released February 1997

When a ferocious plasma storm strikes the entire Bajoran system, Deep Space Nine becomes a port under siege, filled to overflowing with stranded space travelers, unpredictable aliens, and Klingon smugglers. Worf and Odo find themselves tested to the limit as they struggle to control the chaos that has consumed the station. But even greater danger faces Dax and botanist Keiko O’Brien when they must fly a runabout into the very heart of the storm—and encounter a stange new form of life!

Written by Susan Wright

Cast:

- Captain Benjamin Sisko

- Major Kira Nerys

- Constable Odo

- Lieutenant Commander Worf

- Lieutenant Commander Jadzia Dax

- Dr. Julian Bashir

- Chief Miles O’Brien

- Quark

- Jake Sisko

Guest Cast:

Excerpt

Dax believed that one of the best ways to get to know somebody was to go on a long shuttle trip with them. She had figured that out while she was a cadet at Starfleet Academy, where she had been introduced to the concept of the two-person team.

During the past few months, since she had resolved things with Curzon, she was better able to appreciate the fact that she had attended the Academy simply as Jadzia. After being kicked out of the Symbiont Institute on Trill, where the focus had been on generating competition among the Initiates, it was a joy learning how to cooperate with the others.

“Nearing the storm front at ten thousand kilometers,” Dax announced. “How bad is that graviton interference?”

“It’s holding steady now that the bleed has been boosted,” Keiko confirmed.

Dax could already tell that Keiko was a competent technician—their first flurry of stabilizer adjustments had proved that. And her meticulous handling of Ops indicated that she was a perfectionist. But Keiko herself was still a mystery, not only to Dax but to a lot of people on DS9. Maybe even to Chief O’Brien.

“Leeta says you’re going to be on the survey for another few months,” Dax commented. “How is it going?”

“Oh, we’re making progress.” When Dax made it clear she was waiting for more, Keiko added, “Actually we’re working so well together that Starfleet expanded the survey to include the archipelago of the southern continent. We’re finding some rich calcium-complex vegetation that grows in the wet climate along the coast.”

“So you like being on Bajor.”

Keiko smiled at the non-question. “It’s tough moving around with the survey team, never in the same place for more than a few weeks. But the work itself is fascinating.” Then she sighed. “I guess you can’t have everything . . .”

“Why not?” Dax asked.

Keiko looked at her. “For one thing, it’s physically impossible to be on the station and Bajor at the same time.”

Dax concentrated on the helm, letting Keiko’s answer fall lightly into silence. She sympathized with Keiko’s dilemma.

“Was Molly all right when you left her?” Dax asked.

“She’ll be fine.” Keiko acted as if leaving her was perfectly natural, though Dax knew that mother and daughter were seldom apart. “I activated the pony program, even though I swore I’d make her wait until tomorrow.” She checked the chronometer. “It’ll be over soon, and then the nanny program can deal with her. Miles doesn’t know how lucky he is.”

“He didn’t look so happy standing on the service pad.”

Keiko shrugged. “You have to admit it happened awfully fast. He was surprised, that’s all.”

Dax grinned. “I’d say it was fast! He was still trying to ask about radiation levels when you shut the hatch in his face.”

Keiko looked uncomfortable, as if her mask had slipped. Dax remembered the way she had stared at the image of O’Brien on the viewscreen as the Rubicon rose to the launchpad. The chief kept waving until they were out of sight. Only then had Keiko taken a deep breath and returned to the launch sequence.

“I wonder how they’re doing with that freighter,” Keiko said.

Dax checked the station logs. “It’s been secured. But Captain Sisko has issued an evacuation recommendation to all vessels below class two, due to the turbulence.”

Keiko’s eyes widened. “I thought there were no more quarters available on the station.”

“There aren’t.” Dax frowned over the sensor data as the runabout shook from the emission waves. “If the shock waves are this bad out here, what about the turbulence within the storm?”

Keiko glanced at the viewscreen. The pure velvety black mass blocked out most of the starfield, but the leading edge was defined by veins of flashing energy discharge, marking the point where the plasma encountered normal space matter.

“Slowing to half-impulse,” Dax said. “The shock waves are getting stronger.”

“Sensors are calibrated,” Keiko confirmed. “The link to the biometric program is engaged. We’re getting additional data on a wide range of Doppler shifts.”

Dax prepared a burst transmission to send the new data back to the station. Communications would probably be lost once they were inside the storm.

“This close,” Dax said thoughtfully, “I thought we would encounter line and recombination radiation. Even with a reflection level as low as one percent we should be gettingsomething on the interior of the storm.”

“There’s those energy discharges along the edge,” Keiko indicated. “The filaments are being spectrally recorded, but we have no background comparison with the main body of the plasma mass.”

“So we can’t tell if particles are being excited or emitted.”

“It’s an ideal blackbody,” Keiko agreed. “Rate of absorption and emission is the same. I wonder what’s happening inside.”

“My guess is that it’s rotating on its own axis,” Dax told her.

Keiko widened her eyes. “I didn’t think plasma did that in a natural vacuum.”

“Why else can’t we get a fix on the wavelength angles?” Dax had finally thrown out Planck’s law after wrestling with that impossible variable for most of the afternoon, trying to phase the momentum with value of energy release. “This isn’t getting us anywhere. The spectroscopic analysis is giving us the same readings on the emissions that we got on the station—helium, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, calcium . . .”

“It’s the bulk of the interior elements we need to determine,” Keiko agreed.

“All right, here we go,” Dax announced. “Electrostatic field engaged.”

“Spectral index is well within parameters,” Keiko confirmed. “Both waves and particles are being polarized away from the runabout.”

“Prepare to enter the plasma field.”

Dax maneuvered the runabout in a vector that would sharply intersect the edge of the storm. She didn’t want to risk deflection, unsure of the effect that impact would have on the hull. She was also concerned about what might be concealed within the plasma. An ideal blackbody was theoretically impossible without a source of stabilized electric discharge. There was a distinct possibility that a comet-like pulsar or neutron star was at the heart of the storm, and if so, then the gravitational forces could easily overpower the runabout once they entered.

Dax glanced at Keiko, wondering if she should share that nasty piece of information. She had included it in the burst transmission to DS9 because the station needed to be warned of the possibility. But it was too late for them to turn back now.

“Sensors at maximum sensitivity,” Keiko announced. “Prepared for entry.”

“You know . . .” Dax said, “there is a chance the hull could be crushed by the internal turbulence . . .”

Keiko held her gaze. “If the storm is that strong, then the station won’t be able to withstand the pressure either. We need to find out.”

“You’re right about that. I’m taking us in.” Dax hit the thrusters and held on.

But the runabout penetrated the storm without a shudder. Helm control remained steady, while navigational orientation began to swing aimlessly around the chart as if searching for some verifiable indicator to establish their position. Sensors were unable to penetrate the border of the storm.

Keiko switched the viewscreen to spectral/visual. “Look at that . . .”

Inside the blackbody, the plasma was alive. Constant re-ionization released photo-conductive electrons, creating spectral colors within, and even beyond, humanoid sight. Other complex optical effects produced brilliant fluorescent streaks and luminescent flickers of light that twisted and swirled together in the hydrodynamic currents.

Dax slowed the runabout and released a dye marker to give their sensors a ground point. At first she was unsure if they were moving; then she realized the marker was cruising along at about the same speed they were.

She altered their course, concerned about the power spikes as particles and waves struck their electrostatic shields. She reminded herself to watch the relays to make sure the circuits didn’t overload.

“I’ve narrowed the range on the sensors,” Keiko announced. “But the interference is still too great to get anything beyond the most rudimentary readings.”

“That’s plasma for you,” Dax said philosophically. “We need to isolate our targets.”

Using the molecular beam, she released gas particles into the plasma. The computer would track the progress of their collisions and decomposition into charged electrons and photons.

“Keep an eye on the ternary collisions,” Dax told Keiko, indicating the correct equation sequence. “Let me know if the cluster integrals get any larger.”

“They already have,” Keiko immediately replied.

“That fast?” Dax asked, having a look for herself. “This is some plasma storm . . .”

She carefully recorded the thruster action against the movement of the released particles. They revealed an approximate reading of both longitudinal and transverse waves within the plasma, though the splitting of Alfven waves were recorded to the detriment of other variables, filling their data banks with random frequencies.

“Well, according to the gas particles, the plasma is rotating as a mass.” Dax was glad to finally confirm one of her hunches about the storm. “It must be releasing huge amounts of rotational energy, approximately ten to the sixty-seventh power ergs per second. That’s what supplies the relativistic particles and magnetic fields to sustain the storm.”

“It’s building on itself,” Keiko realized.

“That’s right, it’s picking up particles through inverse Compton scattering. That keeps it moving in a steady vector.” Dax returned to her readings. “I’ll see if I can determine the oscillation distribution of the waves. That might give us a base frequency we can work with. But we’ll need to isolate a sample of the plasma.”

“How do you do that with charged particles that are in a constant state of flux?” Keiko asked.

“Usually we’d use the EGD converter. But the plasma is so dense that our power systems can’t create a high enough electric field to contain the stuff.” Dax grimly shook her head. “Maybe we should have brought the Defiant after all.”

“Is there any other way to get a sample?” Keiko asked.

“Well, we could try a plasma trap,” Dax decided.

She spent some time attempting to draw a sample of the plasma into a ring-shaped magnetic field. Despite the high temperatures of the trap, containment of the dense plasma was limited to fractions of microseconds. A bulge kept forming along the lateral surface, instantaneously extending tongues of plasma within the trap and disappearing on contact with the container walls.

“It’s too unstable,” Dax said. “Maybe I can create an open trap using two magnetic mirrors. That might contain the plasma long enough to get a sensor scan on it.”

“Anything I can do?” Keiko asked.

“In a minute,” Dax told her. “Let me just set this up . . .”

Keiko got up to pace in the back of the runabout until Dax called her to return to the sensors.

“I’m establishing the trap in a vacuum field just outside the starboard hull. Look for patterns,” Dax told her, ready to grasp at any straw. “Check number densities, temperatures, electric, and magnetic field strengths. We mainly need to determine the trajectory of relative particles.”

“The ratio of negative and positive charges per unit volume are fairly equal,” Keiko offered. “Though the numbers keep shifting.”

“That’s typical in high-density plasmas.” Dax was preoccupied with the phase ratios. “That’s why we get macroscopic readings rather than the motion of individual particles.”

Keiko sighed and sat back in her chair. “Maybe I shouldn’t have tried so hard to convince Captain Sisko to let me come. I’m not being much help.”

“This isn’t your part of the mission,” Dax pointed out. “It’s mine, and I haven’t been very successful. You’re here because you’re the most qualified person to analyze the data once I’ve gotten it.”

Keiko let out an exasperated sound. “Then why did I have to fight so hard to get the captain’s permission?”

“Benjamin was just worried about Molly,” Dax tried to explain.

“Oh, I don’t blame him for asking about Molly. How could he ignore her when she was practically jumping up and down on his feet?” Keiko turned to Dax. “But what does Miles have to do with it? I mean, really—does anyone call and ask me how I feel every time he crawls into a fusion generator?”

“No . . .” Dax hesitated, but it needed to be said. “Try to look at it from Captain Sisko’s perspective. After all, he did lose his wife during a mission.”

Keiko returned to her console. “That’s true. Don’t mind me; I’ve been like this ever since I left Bajor. I hate to be interrupted when I’m in the middle of a project.”

“Well, then, let’s get on with this one,” Dax said, smoothing things over. “I’m taking us in deeper.”

She engaged thrusters. Temperatures rose as the plasma became denser.

“Here’s something,” Keiko said. “Helix patterns.”

“Where?” Dax demanded. She examined the readings. “Magnetic lines of force. That’s consistent with synchronic radiation but . . .”

“But what?”

“Look at the total heat flux. And the thermal energy transported within the unit area. It’s building, as if there’s some other factor acting on the—”

The Rubicon lurched, and a blinding flash of light shorted the viewscreen. Dax squeezed her eyes shut, covering her face with her hands.

Even when the emergency lights came on, she could barely see through the red spots in her vision.

“Computer is off-line!” Keiko exclaimed.

Dax didn’t breathe until the indicator signaled that the computer core was powering up again. “Electrostatic field remains intact,” Keiko added breathlessly.

That was exactly what Dax wanted to hear. The interior support systems came back on as indicators returned to normal—except for the viewscreen. She would have to replace the circuit buffer first. And increase the repulsion of the electrostatic guard to keep the same thing from happening again.

“What was that ?” Keiko asked.

“I’m not sure. But, look—the sensors recorded the entire electromagnetic frequency range for the duration of the burst.”

“Finally!” Keiko exclaimed. “That gives us the data we need to run a comparison against the biometric models.”

Dax wasn’t as pleased as Keiko. She wanted to know exactly what happened. She slowed the sensor logs and saw what she had been dreading—fifty nanoseconds before the burst of light, a faint luminous current on the order of several hundred thousand amperes had created a stepped leader between the runabout and the plasma. The runabout acted as the ground, releasing an outward discharge, short-circuiting the plasma that was in magnetic flux around them. The white flash had been just one of the secondary results.

“There was a direct energy discharge between the plasma and the runabout,” she told Keiko.

“I thought the electrostatic field would prevent that.”

“Apparently the magnetic currents are strong enough to override our power systems.” Dax considered the readings. “In fact, there’s no way we can compensate for the reaction unless we completely shut off the shields. And the radiation levels make that impossible.”

“If the runabout can destabilize the plasma, what will the station do to it?” Keiko asked. “Will the shields hold?”

“It’s not just the station—what about the wormhole?” Dax countered.

“They might both act as electrodes,” Keiko realized. “That would mean . . .”

“A plasma arc as big as Bajor.”

“With everything in between instantly ionized.” A flicker of her eyes betrayed her immediate thought of Molly. “We have to get back to the station to warn them. Everyone should be evacuated.”

Dax was already activating the helm. “Impact with the magnetic currents could burn out the wormhole permanently. Or the plasma could be caught in its gravitational flux, which means the entire system would be covered by a self-generating plasma storm for the next few centuries.”

“Bajor . . .” Keiko whispered.

Dax couldn’t understand the navigational sequence that she was getting. “We must have been thrown some distance by the discharge.”

Keiko could tell something was wrong. Dax couldn’t find the dye marker, and the angle of the transverse waves had altered.

“That wasn’t just a magnetic field we ran into,” Dax finally concluded. “The currents are being twisted into loops by the cyclonic turbulence. We’ve been transported deep inside the storm. I’m not even sure where we are.”

“We couldn’t have gone far,” Keiko protested. “It lasted less than a second.”

“I don’t know . . . a reaction like that, involving high-intensity heat conduction and Coriolis forces from the rotation . . . it could have produced spacetime variances within the magnetic loop.”

Keiko was also checking the rudimentary readings of the sensors. “Particle and wave density is much higher in this area. And there’s no sign of the dye marker or the gas particles we released.”

“From the number of magnetic currents, I’d say we were much closer to the center of the storm.”

“That can’t be true!” Keiko insisted. “That would be faster than light—”

“Theory of relativity? You might as well forget about that. Our time scale depends on our frame of reference. Inside the blackbody, our only reference is this highly charged, high-temperature energy-matter.”

“But the storm covers nearly half a sector!” Keiko looked as though she didn’t know which way to turn. “It could take us a week to cross it at impulse.”

“Ifwe could figure out which way to go.” Dax watched the particles perform their colored dance, flashing as if they were laughing at the runabout.

“What are we going to do?” Keiko finally asked.

“We’re going to have to find a quicker way out of here. Unless you’re willing to let a plasma storm get the better of us?”

Keiko’s eyes flashed in return. “Never!”

Dax took a deep breath. “Then let’s get to work.”

Leave a Reply

Categories

- Animated Series (60)

- Articles (28)

- Books (447)

- Cast & Crew (79)

- Comics (22)

- DS9 (328)

- Early Voyages (125)

- Education (5)

- Enterprise (373)

- Excelsior (36)

- Food (19)

- Games (223)

- Klingon (70)

- Library (1,543)

- Logs (593)

- Lost Era (55)

- Medicine (18)

- Merrimac (1)

- Mirror (35)

- Miscellaneous (13)

- New Frontier (54)

- Next Generation (635)

- Original Series (681)

- Personnel (436)

- Places (369)

- Politics (12)

- Recreation (10)

- SCE (41)

- Science (1)

- Shatnerverse (9)

- Ships (455)

- Site Updates (98)

- Starfleet Academy (86)

- Stargazer (42)

- STO (61)

- Technology (45)

- Titan (59)

- To Boldly Go (1)

- TV/Film (214)

- Uncategorized (4)

- Vanguard (76)

- Voyager (236)

- Weapons (27)

- Xenology (54)